Most of the time, it takes the witnessing of a disability in order for us to realize the extent to which we take our own ability for granted. Those of us who have no trouble walking rarely think about how we're capable of our own automatic physical transportation--unless we meet someone who's incapable of just that. Physical disabilities manifest themselves in obvious ways that we can automatically relate to, but mental disabilities provide us with further insight as to how the mind works--by demonstrating what happens when it fails to.

Most of us, for example, take for granted our ability to recognize faces. When we meet somebody, we record the most subtle of their features in our minds so we can recognize them again. Their image is imprinted on our minds in a way that's deeper and more detailed than most images. You'd probably recognize a person you just met if asked to pick them out of a lineup of ten people of the same race and gender. You might not recognize a dog or a bird you just saw if asked to pick them out of a group, however. Human faces stick better because we're wired to recognize those within our "group"--family members, clan members, what have you. Animals don't inspire the same sort of memory because we don't recognize them as kin.

But not everyone comes with the same wiring that allows for face recognition. A condition called prosopagnosia, more commonly known as "faceblindness", is the inability to remember specific faces. The condition may arise like amnesia after an incident of brain damage, but approximately 2.5% of people are born with the disorder. No one knows exactly why the congenital version of the disorder arises. It's not a condition that's easily linked to other early childhood developmental disorders, nor does it appear to be symptomatic of anything else. Some people simply see human faces the same way they see the faces of animals--all pretty much the same.

Faceblind individuals generally don't experience the same perceptive difficulties as those on the autism spectrum. They can distinguish emotions just fine, easily picking up on the difference between sadness, anger, or joy. They just don't remember the subtle differences between human faces. They might be able to tell their friends apart, but only by remembering dramatic physical differences, like height, hair color, or distinctive birthmarks. Beyond that, they might not be able to tell if they've known someone for five years or if they've never met.

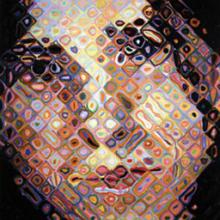

Like certain other neurological abnormalities, faceblindness can yield some beautiful results when addressed in an artistic context. The famous painter Chuck Close is faceblind. You might recognize his work--he's the one who does enormous portraits of the faces of his friends. By rendering faces as landscapes, he explores the way people see the image of a given face. Up close, a Chuck Close painting appears as a series of small dots or other incomprehensible marks. From across the room, a huge, looming portrait of a face appears. He studies the details that most people recognize and memorize automatically, turning his unusual experience into a powerful artistic endeavor.

You can hear more about the experiences of Chuck Close and faceblind neuroscientist Oliver Sacks on Radiolab's podcast about the disorder.